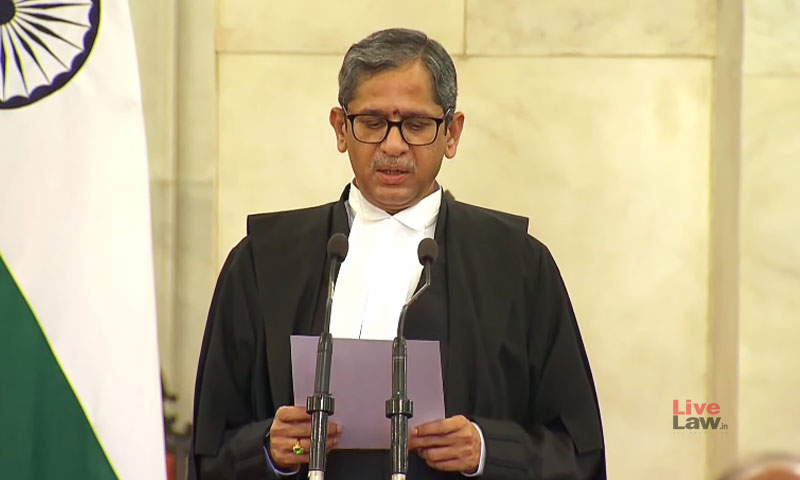

CJI Ramana's Term Raised People's Hopes In Supreme Court, But Left Substantial Issues Undecided

Manu Sebastian

27 Aug 2022 11:42 AM IST

During the 16 month period under CJI Ramana's leadership, one could see the Supreme Court asserting its judicial independence and exercising judicial review powers relatively in a stronger manner.

"I was keen on joining active politics, but destiny desired otherwise", Chief Justice of India NV Ramana said in a recent public speech, much to the amusement of the listeners. It can be said that as the head of the Indian judiciary, CJI Ramana steered the Supreme Court through various minefields with the skills and strategy of an astute politician who knows when to assert and where to concede.

Very often, he gave an impression of trying to do whatever possible amidst the pressures created by a muscular government enjoying absolute majority. Perhaps, he used the cricketing analogy in his farewell address - whereby he said that it is only the player who can fathom the difficulties of the pitch and it may not be possible to hit a sixer every ball as desired by the public - to indicate the constraints within which he had to operate.

There is a widespread consensus among lawyers and commentators that during the 16 month period under CJI Ramana's leadership, one could see the Supreme Court asserting its judicial independence and exercising judicial review powers relatively in a stronger manner, when compared to the terms of previous CJIs.

When Justice Ramana took over as the 48th Chief Justice of India on April 25, 2021, the Supreme Court was facing a severe credibility crisis, due to certain failings during the terms of his immediate predecessors (for more, read here, here, here, here & here). The public faith in the institution was at its nadir then. Though he may not have radically reformed the Court and cured it of all its defects, it can be said that CJI Ramana has managed to change the general feeling of hopelessness about the Supreme Court. At least, it was not a situation where the executive could get away by making brazen statements like "no migrants are walking on the road". As Senior Advocate Kapil Sibal said on CJI's last working day, the government was called to answer, even during the "turbulent times".

On a personal note, as a person who has been tracking the developments of the Supreme Court closely on a daily basis for at least the past four years, I can say that certain unfortunate developments during the previous terms left a sense of despondency with respect to the judiciary in one's mind; on the contrary, CJI Ramana's term encourages one to remain hopeful (critics may still say that this is because of keeping a low benchmark).

Expectations of pro-liberties stance

Before becoming the CJI, Justice Ramana had handled certain matters of public importance, which gave an indication of his possible approach as the CJI as well.

It was the bench led by Justice Ramana which handled the cases challenging the internet shutdown and public curfew imposed in Jammu and Kashmir following the abrogation of its special status under Article 370. The judgment authored by him in that case (Anuradha Bhasin versus Union of India) is notable for its application of the doctrine of proportionality to internet suspension orders and public curfew orders under Section 144 CrPC. The judgment mandated the publication of such orders specifying the reasons. Most importantly, it was declared that internet blockade cannot be indefinite. However, despite the grand declarations in the judgment, the people of J&K did not get a substantial relief out of the judgment, as the Court lobbed the matter back to the Central Government itself for review of the restrictions. The internet restrictions in J&K were renewed periodically, with minor relaxations (2G speed in some districts) granted later, and 4G internet was fully restored over a year after the SC judgment.

Justice Ramana also led the bench which delivered the landmark judgment holding that the restrictions in UAPA will not bar constitutional courts from granting bail if there are violations of fundamental rights due to prolonged delay in holding trial (Union of India vs Najeeb).

Given the nature of these judgments, it was anticipated that Justice Ramana as the CJI would take a pro-liberties stance generally but may not substantively assert it to put the executive in a discomfort in crucial matters (as happened in J&K case). This speculation seems to have been proved right in hindsight. The Supreme Court passed certain powerful orders during this period, upholding the rights of the citizens; at the same time, in several other matters, the executive was given a free pass.

Notable actions in sedition, Pegasus & Lakhimpur Kheri cases

The 152 year old sedition law (Section 124A Indian Penal Code) is now virtually frozen, thanks to a crucial intervention made by CJI Ramana. "The rigors of Section 124A of IPC is not in tune with the current social milieu, and was intended for a time when this country was under the colonial regime", CJI Ramana observed in the order while asking the Centre to reconsider the provision.

The order passed in the Pegasus case also stands out, as the Court resisted the attempts of the Centre to block a probe by raising the "national security" argument. The order written by CJI Ramana asserted the importance of privacy of citizens, recognized the threats posed by illegal surveillance to journalistic freedom, and emphatically said that State won't get a free pass by merely chanting "national security". The Court's intervention exposed the dilly-dallying stand taken by the Central Government in the case and the probe panel also reported to the Court that the Centre did not cooperate. While the judgment has faced some criticism for leaving the matter to a committee instead of the Court taking it up, it must be noted that the direction was in line with the relief sought by the petitioners themselves.

In the Lakhimpur Kheri case, where Union Minister Ajay Mishra's son Ashish Mishra is accused of killing farmers, the investigation came on the right track only after a proactive intervention made by the CJI's bench. The Court reconstituted the Special Investigation Team by including senior officers and appointed a retired High Court judge to monitor the probe. In April this year, the Court cancelled the bail granted to Ashish Mishra, after calling out the State of UP's refusal to challenge the bail order despite a recommendation to that effect by the judge monitoring the SIT probe.

In the matters relating to Tribunal vacancies and Delhi air pollution, the Court showed considerable degree of sternness and put the actions of government under strict scrutiny. The CJI also came to the relief of Jahangirpuri residents by promptly passing a status quo order against "bulldozer" actions, when an oral mentioning of the matter was made.

The initiative launched by the CJI to ensure faster transmission of electronic copies of orders is also laudable. The CJI took this step after taking a suo motu case on the basis of a newspaper report about delay in release of prisoners despite being granted bail as the authorities were waiting for the physical copies of the order.

Article 370, CAA, Hijab, Electoral Bonds : Significant issues sidelined

At the same time, one also gathers the impression that the Supreme Court during CJI Ramana's tenure has been extremely choosy in picking its "battles", as it consciously stayed away from issues relating to Citizenship Amendment Act and abrogation of special status of J&K. In April 2022, when Article 370 matter was mentioned for urgent listing on the ground that local elections are imminent, CJI replied "let me see".

During his term, he never set up a single Constitution Bench to decide pending issues like the validity of quota for Economically Weaker Sections.

There was also a sense of irony when the CJI was zealously pursuing the "election freebies" matter, citing it as an important issue affecting democracy, when the electoral bonds matter was never touched. Although in April, the CJI had given an assurance that the petitions challenging the validity of anonymous electoral bonds would be heard urgently, it was never fulfilled. However, in July-August, the bench devoted considerable time to hear the freebies case, a complex issue involving various policy considerations in the executive and political domain in which the scope of judicial interference seems highly limited. On the other hand, the electoral bonds issue raises several direct questions of constitutional and legal importance, including the money bill issue, and the Election Commission of India is also on record before the Court expressing reservations about the anonymity of the scheme.

Likewise, the hijab case also never got a listing. The petitions challenging the Karnataka High Court verdict which upheld the ban on wearing hijab in educational institutions were filed way back in March 2022. Although different lawyers mentioned the matter before the CJI on several occasions seeking a posting, the matter has not yet been listed. On August 2, when the matter was mentioned for the fourth time, the CJI said that the posting is getting delayed as several judges were unwell and agreed to constitute a bench soon. The matter still awaits a listing. It is quite baffling why the petitions have not got a listing even in the regular course and this points to the need for reforms in the registry as well. On the retirement day, CJI Ramana admitted that he could not pay requisite attention for issues relating to listing of cases and apologised for the same.

Judicial appointments

A remarkable feature of CJI Ramana's tenure is the special push given for filling judicial vacancies. In August 2021, breaking a deadlock of nearly 2 years, nine new appointments were made to the Supreme Court (highest ever in one go), with 3 women judges (another record). One of the new appointees, Justice B V Nagarathna, is likely to be the first woman Chief Justice of India. In May, two more appointments were made to the Supreme Court- Justices Sudhanshu Dhulia and JB Pardiwala. For a brief period, the Supreme Court worked with its highest ever full strength- 34 judges- during CJI Ramana's term.

At the High Courts as well, a record number of appointments were made. In his farewell speech, CJI Ramana said that after he assumed office, the Supreme Court collegium made 225 recommendations for appointments in High Courts, out of which 224 appointments were made(this amounts to nearly 20% of the total sanctioned strength of the High Courts),with a special emphasis on women representation. 15 new Chief Justices were appointed at High Courts.

However, the omission to elevate Justice Akil Kureshi to the Supreme Court, apparently due to the negative perception of the Central Government due to his orders adverse to the political establishment, will loom over the record of judicial appointments as an unredeemed debt.

Increased public visibility of CJI

CJI Ramana was quite prolific in attending seminars and public meetings during weekends and holidays, and his "weekend lectures" have by now become a popular media phenomenon. His quotes on democracy, civil liberties and assertions of judicial independence have often become viral in Twitter, with many users reacting sharply, pointing out the need to "walk the talk".

Nevertheless, he has used the public platform to invite attention to pressing issues such as lack of judicial infrastructure, gender representation in judiciary, need to clear backlog vacancies, improvement of legal education standards, need to simplify judicial process for easy access by the common people, importance of alternate dispute resolution mechanisms etc. Some of his statements carried a particular relevance in the present political context - such as his concerns about the declining standards of legislative debates and shrinking space of political opposition, need to protect diversity and dissent, caution about elections not a guarantee against tyranny.

Two public talks of the CJI deserve a special mention. On April 30, at the Joint Conference of the Chief Justices and Chief Ministers, CJI Ramana did not mince words in saying that executive's failure to perform its functions properly and the ambiguities in laws contribute a lot to the judiciary's load. This statement, made with the Prime Minister in audience, was seemingly a reply to the narrative built by certain sections to discredit the judiciary by citing the level of case pendency.

Also, on July 16, when the Union Minister for Law & Justice Kiren Rijiju expressed concerns at the pendency of cases, CJI Ramana reminded that the executive's delay in filing up of the judicial vacancies was the prime reason for backlogs. Earlier also, CJI has highlighted the unfairness in targeting the judiciary alone for the problem of pendency, as it is a larger institutional problem. In the April conference, speaking before the Prime Minister, the CJI said that the pendency is blamed on the judiciary but the issue of unfilled vacancies and increasing sanctioned strength of judges need discussion.

CJI had also passionately pursued the idea of a dedicated body for judicial infrastructure, a National Judicial Infrastructure Corporation, which will oversee the utilisation of funds for judiciary. However, there was no consensus for this proposal at the Chief Minister's conference.

Highs and lows

During the term of CJI Ramana, one witnessed certain remarkable instances of judicial review by the Supreme Court - such as the interventions made in the suo motu COVID case for ensuring availability of vaccines and medical oxygen, the monitoring of disbursement of COVID compensation, series of directions passed for welfare of COVID orphans- and also certain laudable judgments protecting fundamental rights (such as Md Zubair, Satender Kumar Antil cases). At the same time, one could also see the Supreme Court hitting the low-point during the same period through certain extremely problematic judgments which put the fundamental rights of citizens at peril (for eg, the adverse remarks in the Zakia Jafri case which led to arrest of Teesta Setalvad and RB Sreekumar, the judgment allowing criminal prosecution against activists who sought SIT probe into alleged killings of Chattisgarh tribals by armed forces, the PMLA judgment etc). CJI Ramana was not a party to any of these judgments/orders.

The judgments in Zakia Jafri and PMLA cases caused a lot of public despair. So much so, veteran lawyer Senior Advocate Kapil Sibal declared at a public function that he has no hope left in the Supreme Court.

However, certain actions of the CJI Ramana during his last week perhaps show that it is too early to lose hope. One is the notable judgment delivered by him striking down certain provisions of the Benami Transactions Prohibition Act, which is a good precedent against arbitrary penal law provisions having potential for abuse. It will be interesting to watch for the impact of this judgment on the PMLA verdict. In fact, CJI Ramana's judgment expressed certain reservations about one aspect of the PMLA judgment. Two, the swiftness with which the CJI decided to re-examine certain aspects of the PMLA judgment in review is quite reassuring. Three, he promptly listed the petition challenging the remission granted in the Bilkis Bano case and sought for a reply from the Gujarat Government. Four, he revealed the key findings of the Pegasus probe panel, including the fact that the Government of India did not cooperate with the inquiry, though the report as a whole was not published, possibly in the light of the committee's statement that the persons who submitted their devices requested for keeping the contents confidential. The Pegasus case is now left for a future bench to decide.

CJI Ramana is not without failings and deserves criticism for delaying decisions in many substantial issues. However, it has to be acknowledged that he has taken efforts to sustain the public faith in judiciary from completely dying out. The Supreme Court has indeed shown during this period what it is capable of doing to protect the citizens' rights when our country is going through challenging times (think about the Md Zubair Case). So, probably the message from CJI Ramana's tenure is - don't give up the hopes on judiciary completely. A complete discrediting of the Courts is a subversive exercise as it will only aid the forces working against the Constitution.

(Manu Sebastian is the Managing Editor of LiveLaw. He may be contacted at manu@livelaw.in. He tweets @manuvichar)